It’s easy to forget when we live in the age of the pocket supercomputer. It’s easy to brush aside as interesting but altogether unexciting when Holywood has shown much more exciting adventures. It’s easy to look upon those iconic photographs and feel a bit impassive to them because it’s all a bit… old hat. What’s a grainy picture of a distant Earth as seen from the surface of the Moon when we have a constantly live-streaming 4K feed of this place we call home, as seen from the International Space Station?

When three astronauts blasted off from Kennedy Space Center in July 1969, the world was a bit different. I’m a child of the 80s so, obviously, I wasn’t there. But I’ve spoken to my Dad who was watching on his black and white TV at the age of 12, as Neil Armstrong descended the wiry steps of the Lunar Module and touched down on the dusty grey surface of the Moon. In an instant, it changed the mindset of the world; look at what we can achieve as humans when we work together. It shifted the boundary of what people accepted as possible.

What fascinates me about the space race is the overwhelming unlikelihood of it all. I was there in 2012, watching as Felix Baumgartner sat in his little capsule and, at an altitude higher than any other human had ever been*, jumped out and fell to the ground at a speed of roughly 843.6mph. The macabre thrill of watching the painfully slow ascent and rapid descent, combined with the “will he, won’t he” risk of what could be the demise of a person on live TV, gave a semblance of what it might have been like to witness Apollo 11’s journey to another celestial being, but it can’t quite come close. Because back then just being able to contact your family on a crackling, rudimentary telephony system was a struggle.

You can sort of (vaguely) see why some believe the moon landings are faked, because the colossal wave of information that is revealed upon lifting the lid on the mechanics of the moon landings, can make your head hurt. Typically, a good place to start the rational thought process is to compare then to now; perhaps comparing the computing power of the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) to technology we have today. In fact, it might be even more thrilling to discover that the modern smartphone in your pocket, pinging every other minute to let you know you’re dehydrated, has more computing power inside that sliver of metal and glass than the whole of NASA in the 60s. All of it. It’s a quick and dirty way to get some perspective, and of course the AGC wasn’t about raw computing power, rather it was more capable and reliable than it was powerful, but the fact remains - things have moved on a little bit since then. Yet that computing power in all of NASA managed to stick four feet on the lunar surface and bring them home again.

This is what gets my motor whirring: clever people were able to invent systems, methods, procedures and materials to launch three Earthly beings up into the vacuum of space, execute various detachments and reattachments of fabricated spacecraft bits whilst orbiting around Earth, power out of Earth’s orbit and travel over the 384,400km between Earth and the Moon, orbit around the Moon, detach some of those spacecrafty bits, fly down to the lunar surface, walk around for a bit, gather some samples, do some tests, get back into the spacecrafty bits, blast back up to the remaining bits still orbiting the Moon, connect back up, rocket out of the Moon’s orbit back 384,400km to Earth, punch through the Earth’s atmosphere at the correct geolocation, whilst the Earth rotates at 1,000mph, without getting skimmed back into space again or burning up, and gently splash into the sea, without killing any of those three Earthly beings and not hitting anything on the way... and breathe.

Now, in each of those phases there are hundreds of thousands of words to be written, and have been written, but at any point in any one of those transitions, for any number of truly trivial reasons, something could have gone wrong and it would have been the end for those three astronauts. No alternative plans, no rescue protocols - just a millionth of a second between life and death. A door not properly sealed. An oxygen tank not releasing its life-extending contents. An engine not starting. A switch not soldered correctly. A rip in a spacesuit. A miscalculation of any kind. Anything.

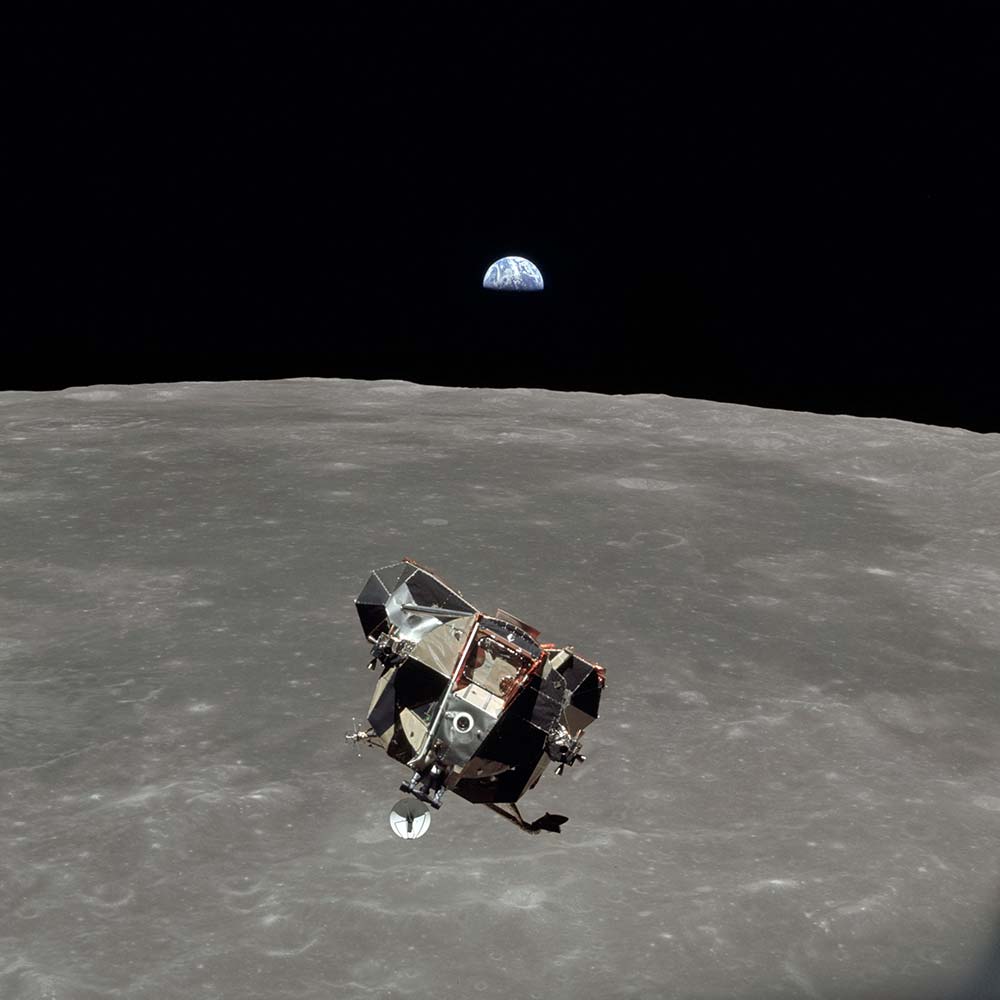

And yet those three astronauts, Neil Alden Armstrong, Edwin Eugene “Buzz” Aldrin Jr and Michael Collins, did make it all the way there and back again. They did do all of these things and more, and did it under the captivated eyes of the world. They weighed up the risks, the almost certainty of death along the way, stood at the threshold of the Saturn V rocket and committed themselves to the furtherment of humankind’s collective nous. For me, not even the glint in anyone’s eye at this point, I can only rely on archival footage and accounts of what it was like to watch this unfold in real time, and to this day the very best example of how it must have been is watching the documentary film “Apollo 11”, directed by Todd Douglas Miller. If you had to watch one thing that sums up the unbelievable, and I mean that in the full sense of the word, achievement of the Apollo 11 mission, it’s this. The film is 93 minutes long and documents, using only archival 65mm footage unearthed recently, lovingly threaded together to create the narrative “behind the scenes” look at the Apollo mission from pre-flight planning all the way through to completion. I was absolutely glued to the screen from the moment the wobbly Universal logo swished around in retro fashion. But a 4-minute sequence 2/3rds of the way through is what made me suddenly appreciate the scale of their achievement, and to be honest, made me quite emotional. Shown in almost real-time, we watch as the surface of the Moon scrolls past our view before suddenly a little black dot appears. This black dot gets bigger and bigger until we recognise it as the Lunar Module. Bigger it gets until we can read the little facets and legs and windows. Bigger still, closer still. Then we witness the true magnificence of this whole thing - the two dock together in a smooth dance of absolute precision.

I was emotional because at the heart of this story are three guys who worked their absolute hardest to put themselves in the position of maximum risk for maximum collective gain, and each one has their own individual stories to tell. They had achieved something no other person had ever achieved, captured photographs that redefined what it was to be an inhabitant of Earth, and moved the boundary of what is possible. For the two that landed on the moon there was a once-in-humantime experience and you can see in the farewell TV address from space that, for Armstrong more than Aldrin, it was quite an emotional moment. For Michael Collins, orbiting in the Command Module, there was an entirely different experience. Responsible for maintaining the Module for the two returning astronauts, as well as resting himself for the various high-intensity manoeuvres that were required at re-connection, he spent his time orbiting the Moon 30 times, relaxed and excited. At one point as he flew around the dark side of the moon, he was the single most distant person from all of human history there had ever been, but insists that he never felt lonely. He didn’t know if he’d ever see his pals again and there was the very real prospect of having to pilot the Command Module down to meet the Eagle by himself. He didn’t know if he'd make it home again and if he did, would he be accompanied with his comrades, or would he be the sole survivor. All incredibly challenging emotional states to find oneself in.

But this sequence, in all its tension-filled glory, showed the most important incremental step to getting back home; with the Eagle and Command Module reattached, forming Apollo 11 once more, they set course for Earth. Yet in that sequence you are only shown the headline of what must have been an incomprehensibly complex task. To take a Lunar Module that was resting on the lunar surface, in an environment never before experienced by anyone and thus all of what humankind knew to that point was based upon assumptions, and not just get it back into the vacuum of space again, but rendezvous accurately enough with another man-made object flying around that same lunar surface at 3,600mph, and connect the two together again without any mistakes… as a mental elasticity exercise, this is pretty damn close to snapping my brain. Yet they did it all with a computer that was 4 million times less powerful than your smartphone.

The Apollo 11 mission is an onion of arena sized proportions that, as you peel off each successive interesting subject layer, it reveals yet more layers of complexity. You can spend many months in any of these fascinating layers, figuring out what everything means and why it was done and who invented it - it’s a ludicrously impressive adventure of almost unfathomable proportions. It’s hard not to be inspired by it all and the general acceptance that it was humankind's greatest achievement is only offset by the lack of progress since. Perhaps not in a space-going sphere, because we all watched as Elon Musk shoot a rocket into space with a Tesla car as payload, complete with space-suited mannequin sitting in the driver's seat, in the most grotesque display of egotistical space junk since the 1988 film Moontrap**. The ability to go to space is indeed more achievable now than it has ever been, but mankind and the collective acceptance and celebration of what we can do together, has not progressed. I watch in archival footage the worldwide connectedness that followed the witnessing of the Apollo 11 mission and the potential for change that it wielded, and then switch over to the latest news of conflict and division for no other reason than a few of these Earthly inhabitants considering themselves better, more powerful, more important than others.

Each time I dip into the world of the space race and the Apollo missions, I am left in awe of all of what NASA managed to achieve. I am captivated by the documentaries that present the good, and the heartbreakingly bad, that each mission entailed. The frustratingly short series on Netflix called “Challenger: The Final Flight” would leave only the most cold of heart unaffected. At each turn there’s more and more inspirational figures ready to impart their own experience and what’s more, in each of these documentaries and interviews there is one undeniable common trait: they all have a logic defying humbleness. That’s the truth of it all; only a few very clever, hugely experienced people get to do it (unless you have more money than sense, see aforementioned Musk, but also Branson and Bezos) but those who head to space for the collective advancement of humankind want nothing more than to share their experience with the world. I can’t help but be drawn in completely.

It’s a searing indictment of a politician's tendency to place political (and personal) gains before all else that the Apollo programme was created, defunded and cancelled before all planned missions were completed. Travelling to the moon was absent in John F. Kennedy’s goals as President at first - too costly and nothing to gain politically - but having presided over a botched Bay of Pigs invasion, and seeing Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person in space, his chance at redemption welcomed the approval of gigantic budgets to allow their side to reach the moon first, bolstered by his now infamous speech:

“We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.”

But despite the effort of unmatched proportion to actually achieve that very thing, by the time it was achieved a new administration was in power, and the priorities did not match those of the preceding admin. Thus it would become too trivial and costly for space flights to continue - the emphasis shifted closer to home for space related endeavours, with the launch of the STS programme and the International Space Station. After Apollo 11 returned and successfully splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, the underlying “need” for the space programme was gone; President Nixon, fulfilling the objective set by JFK, saw no reason for any more moon visits; technological and scientific research played second fiddle to Cold War one-upmanship and America had inarguably “won”. The Apollo programme, owing to the space race being won and political statements made, as well as lacklustre support from the public, fizzled out after Apollo 17 - just 12 astronauts would visit the moon. Funding the Apollo programme was hugely expensive - multiple billions of dollars - and the court of public opinion, seeing no gain in going back to the Moon, brought a close to one of the most exhilarating and fascinating periods of human’s trajectory. Interestingly enough, looking through the original plans for the future of space travel, there were plans to establish a permanent moon base by the late 70s and onwards, in a crewed mission, to Mars by the late 80s. Imagine if plans had remained, where we’d be now. Would we have colonies on Mars? Would those imagination igniting depictions of bustling communities stationed on Mars be a reality now? It’s fun to imagine.

*this has since been furthered by Alan Eustace

**This was a film I watched as a younger man, and thought it quite exciting. Watching it as an older man, it's very much not.

4 comments

BBC podcasts on A11 and 13, also using a lot of archival material, are fascinating listening

Great read. Astro, great product

Amazing read – thanks for sharing Gordon. I couldn’t agree with your final sentiments and also wonder that myself – where would we be now had space exploration continued on the same trajectory as Apollo 11.

You’ve seen Moontrap? And I thought it was only me 😁